July 14, 2016

On Tuesday, July 12, local ed reform group, MinnCAN, hosted a “stakeholder learning and  planning event,” in connection to the federal government’s revamped education policy–the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). MinnCAN billed the session as a “chance to learn more about the possibilities under ESSA and hear about the priorities of local community leaders.” (I attended at the invitation of a friend.)

planning event,” in connection to the federal government’s revamped education policy–the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). MinnCAN billed the session as a “chance to learn more about the possibilities under ESSA and hear about the priorities of local community leaders.” (I attended at the invitation of a friend.)

To host the event, MinnCAN presented a united reform front, partnering with Educators 4 Excellence, Students for Education Reform and Teach for America- Twin Cities–-all national groups with admirable infrastructure and event-hosting budgets. This one–held inside the Minneapolis’s Sheraton Midtown hotel–included muffins and coffee, as well as a smattering of folks from the reform groups listed above, and also from the Minnesota Department of Education and various local political advocacy groups.

While there, I sat next to a friendly young man, who turned out to be a note-taking rep from MinnCAN’s parent company, 50CAN. Aside from a minor scuffle over VAM, or “Value-Added” teacher evaluations–which the 50CAN guy insisted were scientifically valid, and only “politically” unpopular, after I referred to VAM as “junk science“–things went smoothly. Here are some highlights:

Education What?

MinnCAN’s presentation was run by someone named Bill Porter, out of Portland, Oregon. Porter explained that he works for a group called “Education First,” and was brought to Minneapolis by the Chicago-based Joyce Foundation.

The Joyce Foundation has a market-based reform rap sheet a mile long, with a list of grantees that include such hat-in-hand (not!) groups as LEE (TFA’s policy offshoot), Minnesota Comeback (sitting on a cool $35 million) and, sadly, the Education Writers Association. Goodbye, Fourth Estate!

Education First has a very attractive, easy to navigate website with lots of handy info. The ESSA bill, which passed in 2015, and is a long overdue rewrite of the toxic, NCLB law, is more than 1,000 pages long. The only person I know who has read it, in its entirety, is Louisiana blogger, Mercedes Schneider. Thus, it would be easy to conclude that Education First is providing a handy service to citizens by condensing the War and Peace-like ESSA into digestible, PowerPoint bites.

But, Education First is an advocacy organization, with a funder-pleasing point of view to sell. Putting that aside, the emphasis of Porter’s presentation was subtle–and focused mainly on “opportunities” for states, the oft-cited need for “stakeholder input” and so on.

Testng

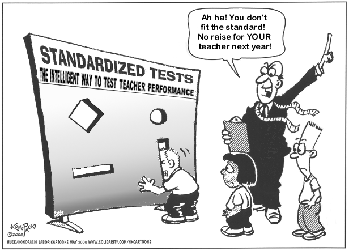

- Education First, through Porter, clearly supports ESSA’s continued insistence (fought for by Democrats, no less) that all children, in grades 3-8, must be given yearly standardized tests. During his presentation, Porter reminded the audience that states are still supposed to test 95 percent of their students, and he advised Minnesotans to “help ensure students ‘opt-in'” and not out, of testing. Part of the argument, Porter said, is to make it clear that the tests are providing “really rich data, and people shouldn’t have the option to just say they don’t care.”

- Punishment? When questioned, Porter agreed that there are no known consequences for districts where less than 95 percent of students get tested. (The opt out option lives on!) However, it seems clear that the testing lobby, run mostly by Pearson, has won a victory with ESSA, since districts will still need to sit kids in front of computer screens or bubble sheets in order to prove every one of them is “succeeding.” (Here’s a look at what’s different about testing, for now, under ESSA.)

- John King Alert! (This did not come up in Porter’s presentation, but is quite important). ESSA supposedly provides some relief from testing (by allowing states more flexibility with how to use test results, etc.), BUT, United States Secretary of Education, John King, is currently working–through the attempted passage of “regulations” that would go along with ESSA–to force states to comply with the one-off, “summative” test-and-punish system that epitomized NCLB. Example: The language in proposed Regulation 200.15 (find it here) is quite authoritarian, and tries hard to insist that ALL students must be tested, or else. King also wants to judge schools on an A-F scale, according, primarily, to test scores. Disagree? You have until August 1 to read the regulations and comment on them.

New Money for Teacher “Academies”

- Porter’s presentation introduced but did not dwell on this golden ticket, nestled within ESSA. Two percent of a state’s federal money can now flow to start-up teacher training sites, to fill those talent pipelines everyone is so crazy for, Until now, most teachers have had to get certified at an institution affiliated with a university of some sort. Now, this “monopoly” may be on its way out, according to the “elitist” Brookings Institution:

A less-noticed new provision in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) may be critical to unlocking business model innovation in teacher preparation.

- Think of this as deregulation for the teacher licensure field (long a goal of the privatization-based reform movement). Under ESSA, states can divert federal, taxpayer money to “authorize new ‘teacher preparation academies,'” to be set up and run according to free market rules (or lack thereof). For example, according to the Brookings Institution:

…states that authorize these academies (will be required) to eliminate “unnecessary requirements” for state authorization, such as requiring that faculty hold advanced degrees or conduct academic research, that students complete a certain number of credit hours or sequence of coursework for graduation, or that preparation academies receive institutional accreditation from an accrediting body.

- The idea for all of this reportedly came from the New Schools Venture Fund, a California-based “venture philanthropy firm” with a penchant for lavishing funds on such “innovators” as TFA, the Rocketship charter school chain, and Match Charter School. From the online journal Ed Week:

The idea is a bit like the “charterization” of ed. schools. It’s the brainchild of folks at the New Schools Venture Fund, and it has in its mind’s eye programs like the Relay Graduate School of Education, the Match Teacher Residency, and Urban Teachers.

- The lobbying group that fought for this provision (which debuted a few years ago, as the failed GREAT schools Act) is a collection of nine charter school-friendly groups such as TFA (they’re everywhere!), and the Relay and Match “charter-ready” teacher training programs. (Here’s a 2011 article on this “transformation,” from the New York Times.)

The slideshow Porter gave prompted some discussion and questioning, but was mostly absorbed without comment from the crowd. When he finished, Minnesota Department of Ed employee, Stephanie Graff, whose career path typifies TFA’s reach into policy making positions of power, gave more info about how the Gopher state would begin implementing ESSA with, again, the requisite “stakeholder” feedback.

One woman in the crowd asked for the materials on ESSA to be first translated into Minnesota’s “four major languages,” (which she did not specify)–so that parents could get themselves up to speed on the new law before attending a presentation on it.

This kind of exchange was the most “rigorous” of the day, with staffers from groups such as the Minnesota Education Equity Partnership pressing Graff, et al, to rethink their community engagement plans. Graff took the heat well, and promised to be easily accessible via email and phone. (Participants could, for example, help steer Minnesota towards a broader definition of what success looks like; the state could even choose to implement a pilot program in using alternative, performance-based assessments.)

The best moment for me came when a woman openly questioned ESSA’s emphasis on putting “highly effective” teachers in every classroom, based on student achievement (er, test score) gains.

She asked if there Is any distinction made between “great” and “highly effective” teachers, before making this point: “Some teachers aren’t great on paper, but are very effective at reaching certain populations.”

Coupled with the continued testing and accountability fetish are dangerous provisions that will serve to diminish the quality of the teaching workforce in favor of a competitive teacher preparation market, whose graduates’ worth will be measured by their ability to raise student test scores, and little else. So although federal education policy now operates under a new name, in the ESSA we still have the same testing, conceived within the same neoliberal framework.

–Wayne Au and Jesslyn Hollar, “Opting Out of the Education Reform Industry“

No grant, no guru, no outside funding source. My work is entirely funded by my very kind and generous readers. Thank you to those who have already donated!

[Exq_ppd_form]