March 29, 2016

Two key education reform strategies being implemented in the Minneapolis Public Schools withered a bit yesterday, after being exposed to some data-driven sunlight.

First came a policy brief published by the National Education Policy Center (NEPC), based at the University of Colorado-Boulder. The NEPC, which casts a welcome, skeptical eye on today’s “transformational” education reform ideas, zeroed in on the “portfolio” district model, which Minneapolis has been operating under since at least 2010.

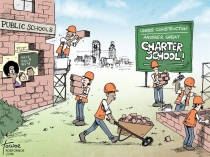

The portfolio model is rooted in the principles of the stock market, where “underperforming” stocks–or schools–will be quickly shed in favor of different stocks, or schools, that promise to yield better results. The goal is profit, in the stock market, and “high performance” in the school district realm. Paradoxically, the education policy that accompanies this approach promises more freedom (“autonomy”), while insisting that schools adhere to standardized, pre-determined measures of success (test scores).

In Minneapolis, we are seeing this through the district’s promotion of “Community Partnership Schools,” heavily touted as a way to empower schools and encourage success–as long as the schools jump through someone else’s “accountability” hoops. But the NEPC brief does not simply swallow the portfolio rhetoric, even as it acknowledges that “given the struggles of urban school districts, no proposal should be easily dismissed.”

Instead, the NEPC encourages policy makers to look beyond the “spin and cherry-picked data” that has accompanied the portfolio district model (brought to Minneapolis by the national ed reform advocacy group, Center on Reinventing Public Education).

A significant problem, according to the NEPC, is that portfolio models have been sold as a way to “overcome problems of poverty and structural inequality and under-resourced schools” only through “changes to the school management structure.” A portfolio approach to school reform does not naturally confront the deep “societal inequities” that have created great concentrations of poverty in urban districts, and instead, expects schools to close gaps without additional state funding or economic policy support.

And, it can cut out democratic decision-making, often by replacing or overriding elected school boards and state government, and putting schools in the hands of private operators or funders– mostly at the expense of poor communities of color (whose voting rights are also currently under attack in many states, as the NEPC policy brief points out).

We can see this happening before our eyes in Minneapolis, through the growing influence of MN Comeback–the privately funded, privately managed group that says it would like to completely “remake” Minneapolis’s public school system, primarily by funding the Community Partnership Schools/portfolio plan–minus public oversight.

MN Comeback is part of the billionaire-funded, Memphis-based group, Education Cities. On March 22, Education Cities published an “Education Equality Index,” designed to “measure and compare schools, cities, and states” according to student test scores. It seems the idea was to celebrate a handful of “gap-closing” miracle schools, where low-income kids are performing well on standardized tests–frequently in charter schools. This fits the narrative most likely to be supported by Education Cities’ funders, including the Walton Family Foundation, whose love for charter schools is legendary.

Sounds great, right? The problem is, Education Cities’s methodology–described as “junk” by Rutgers University professor Bruce Baker–was flawed, and has since been retracted through a contrite press release that went out on March 29. Behold the cumbersome backtracking:

Education Cities and GreatSchools have identified limitations in the interpretation of state-level Education Equality Index (EEI) scores. Our goal is to highlight states, cities and schools that are more successfully closing the achievement gap than others. We are confident that school-level and city-level EEI scores are highlighting success stories across the nation, but we have concluded that the state-level EEI scores are not the best way to compare states. Because states’ absolute EEI scores are highly correlated to the percentage of students in the state who qualify for free and reduced-price lunch, we have removed the rankings of states based on the EEI score and pace of change pending further review.

It turns out that ranking students according to test scores is not as easy as it sounds, especially when the goal is to compare kids in different states. All poor kids are not the same. All tests are not the same. Different states have different tests, with different cut scores, throwing into question who is really a “high performing” poor kid and who is not (the question is never whether or not we should have so many poor kids in the first place…). All of this makes turning kids into data points on a graph really tricky, which was quickly uncovered by consumers–and even presumed supporters–of Education Cities’ index.

The embarrassing flaw in Education Cities’ report was that their use of data made it look like states with higher numbers of poor kids were “doing better” than states with fewer kids in poverty. That’s because poverty impacts test scores. A state with more kids in poverty is going to have a lower “achievement” gap, because it will have fewer high performing test takers, overall.

This is why the NEPC policy report recommends states resist grasping for miraculous ed reform strategies, such as charter schools or portfolio district models. Instead, William Mathis and Kevin Wellner, who authored the report, argue that an “equity-focused” approach to boosting urban schools makes more sense, and should involve, first and foremost, adequately funding schools.

Minnesota lawmakers are currently weighing how to spend a $900 million “surplus.” So far, it seems Governor Mark Dayton is the only one who wants to spend the bulk of this on education, with Republicans pushing for tax cuts and Democrats prioritizing transportation needs, meaning the “adequate funding” of Minneapolis’s schools might not be happening anytime soon.

Most importantly, however, all the evidence suggests that no governance approach will come close to mitigating the harms caused by policies generating concentrated poverty in our urban communities. In light of this core truth, does it make sense to privatize the management of urban schools?

—NEPC Portfolio Schools Policy Brief

No grant, no guru, no outside funding source. My work is entirely funded by my very kind and generous readers. Thank you to those who have already donated.

[Exq_ppd_form]